I’ve told my students that the word “history” comes from the Greek “historia,” which means “to learn by asking questions.”

For my US History students, they are exploring the question of what happened on 9/11. We looked at materials in class (including video from MSNBC’s live coverage on 9/11 in 2001) and talked about some of what happened. And now I’ve asked students to interview someone who lived through 9/11.

The purpose of this assignment is threefold:

- to learn more about 9/11 from someone they know

- to practice taking an oral history — later in the course, students will conduct many oral interviews as part of a “family history project” (FHP)

- to create a historical artifact — they will record the time and place where they conducted this interview, and when they write it down, it will be a record.

To prepare for their interview, I had them interview me in class. I was living in Washington, DC, when 9/11 happened. I also knew two people who died on that day — Andrew Curry Green (the husband of a former teaching colleague) was on Flight 11, and Stuart Meltzer (a friend from elementary and middle school) worked for Cantor Fitzgerald, and was at work above the 100th floor of the North Tower when Flight 11 hit.

My students knew of some quality transcription apps that will serve them well when they do the FHP in second trimester. And in class on Tuesday and Wednesday, they will conduct a Zoom interview with a friend of mine who lived through 9/11 here in the Triangle; she experienced prejudice because she is Muslim.

So that’s one way to “do” history — through oral history. We will have to get more creative when we go back five or six hundred years (or more) and look at events from roughly 1450 to 1750 in our first proper unit of “US History” — we had been in an introductory unit.

We will start that unit by a visit from UNC students who are also indigenous peoples, and who can give us their perspective on US History. Then we will look at Europeans and Africans and how people from those three continents interacted on the land known today as the “United States.”

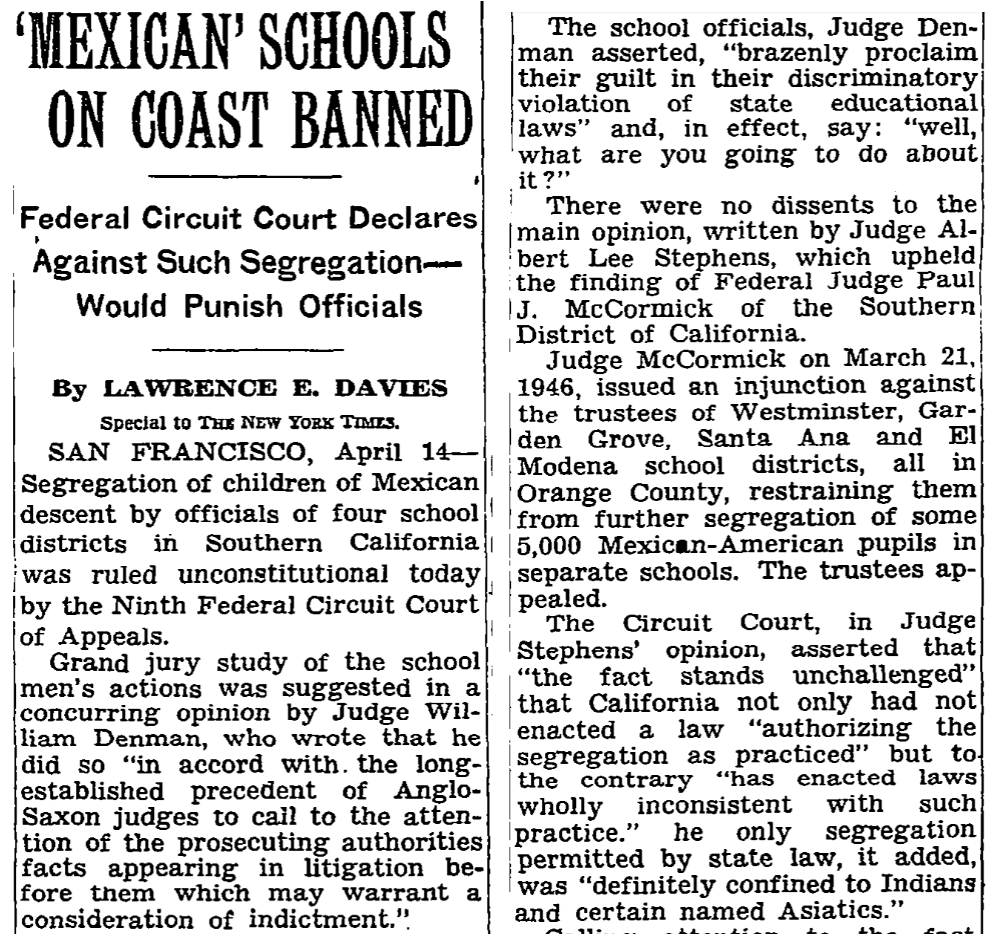

In my “Holocaust and Other Genocides” seminar, we are learning the basics of the Holocaust by examining a few people’s stories and by looking at chronologies and maps.

Three of my students had an opportunity to interview Shelly Weiner, an 85-year old Holocaust survivor who lives in Greensboro, NC. They talked with Ms. Weiner via Zoom for nearly an hour, and they are working on a profile of her that will be published in the NC Holocaust Council’s “Back to School” newsletter in a few weeks.

In the process of writing that profile, a question came up — Shelly is from a town called Rivne in Ukraine, and Shelly reported that 17,500 Jews in Rivne were murdered in three days in November of 1941.

That’s a mind-boggling number to think about.

There are just 1,440 minutes in a day, so that means there are just over 4000 minutes in three days. That means more than four Jews were murdered per minute for three days. That’s one murder every 15 seconds.

When I saw that number — 17,500 Jews — I wondered what percent of the Jews in Rivne that represented. I imagined it was a good number, but I wasn’t sure if there were closer to 20,000 or 30,000 Jews before that awful massacre.

In the process of exploring that question, I came across a powerful source — a 100+ page book titled Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941.

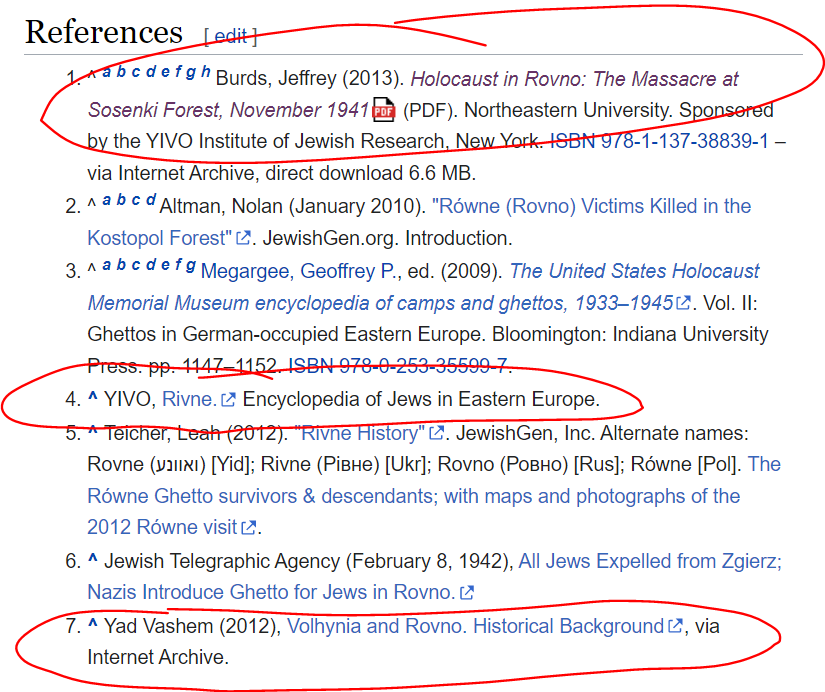

This is an interesting case of how Wikipedia can lead you to remarkably good resources. The Wikipedia page about the Rovno Ghetto is short and contains a bit of information. It says that:

On 6 November 1941, about 21,000 Jews were massacred by Einsatzgruppe C and their Ukrainian collaborators. The remaining Jews were imprisoned in the ghetto. In July 1942, all remaining 5,000 Jews were trucked to a stone quarry near Kostopol and murdered there.[1][3]

Now that’s not terribly helpful. It also says 21,000 Jews were massacred, which is different from the 17,500 I’ve seen in other sources. And it also makes it sound like all the killing was done on one day — November 6, 1941. Don’t rely exclusively on Wikipedia. But do USE Wikipedia…

Because its list of sources can be excellent — and source #1 from this particular Wiki article led me to the remarkably powerful book about Rivne, written by a professor at Northeastern University in Boston, Jeffrey Burds.

What some students might not know is that in Wikipedia, if you hover over a source number (in this case, source #1), it pulls up the reference.

So I went to the full list of sources at the end of the Wikipedia article…

And as my red circles indicate, at least three were solid sources.

So I spent about three hours this morning “doing history” — learning more about Rivne than I ever had before. I mainly read pages and pages from Professor Burds’ book — and I’ll paste a particularly powerful segment from his book at the end of this post.

** Note — I emailed Professor Burds this morning (Sunday, Sept 11) to say how much I got out of his book and to wonder if he might be able to answer questions with my students. I did not plan to write about this because I figured he’s busy and he might not get back to me for a few days, if at all. In fact, he got back to me 11 minutes after I emailed him — here’s what he said:

As students dig into more extensive projects later in the course, I will strongly encourage them to do their homework and then reach out to professional historians to help them learn more. It should not be “can you do my assignment for me?” but “I read your article and saw a video of you talking about your book, and here are three questions I have for you…”

I look forward to having Professor Burds speak with my students in the near future!

I learned far more information about Rivne this morning than will fit into a profile of Shelly Weiner. But that one question — what percent of Rivne’s Jewish population did those 17,500 people represent — led to some real historical research.

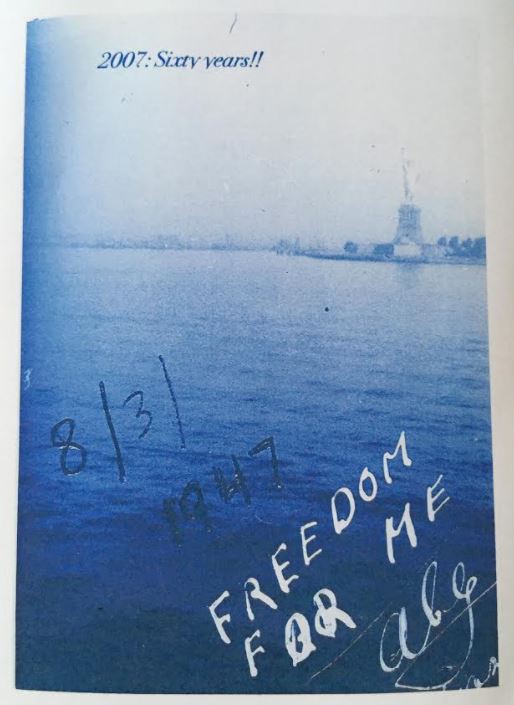

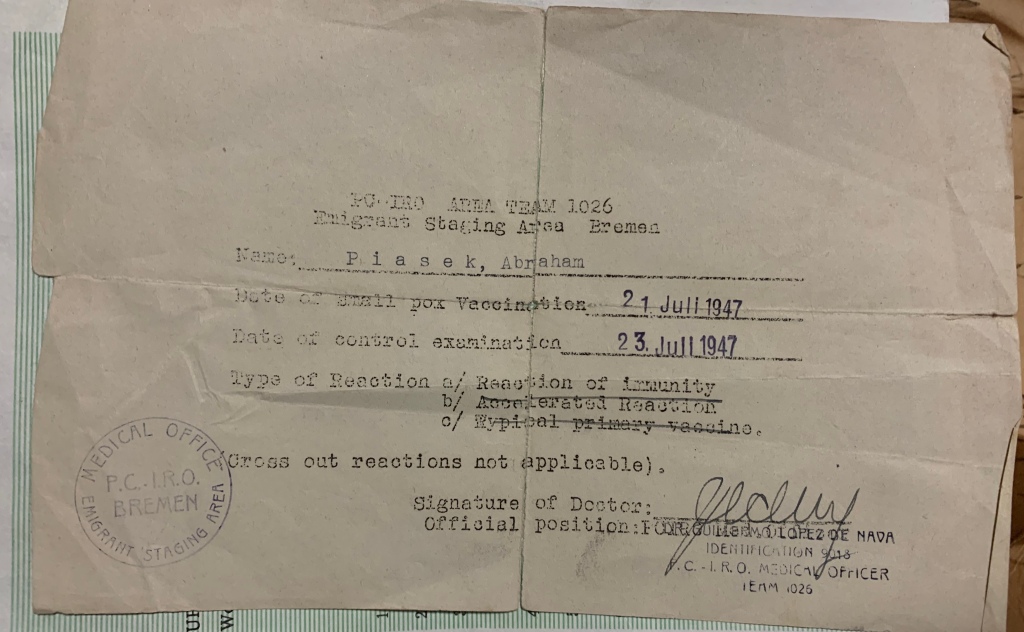

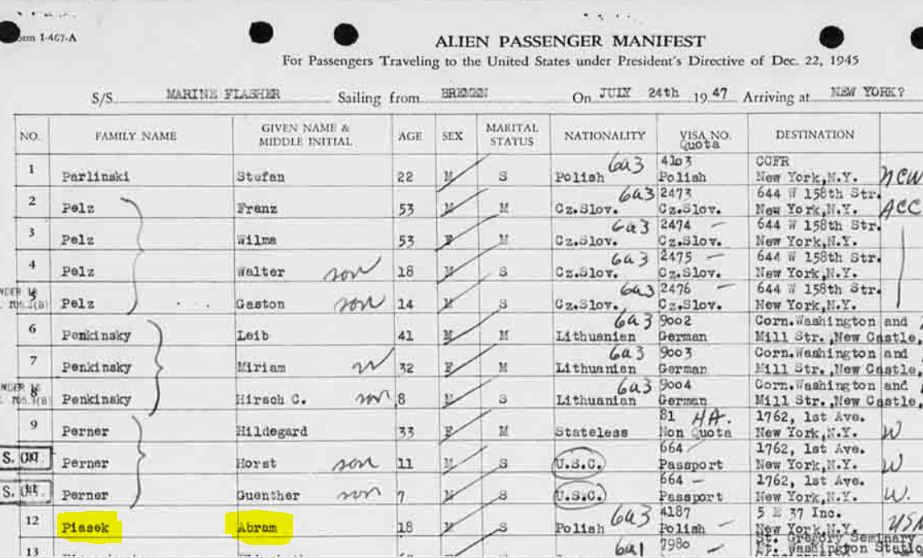

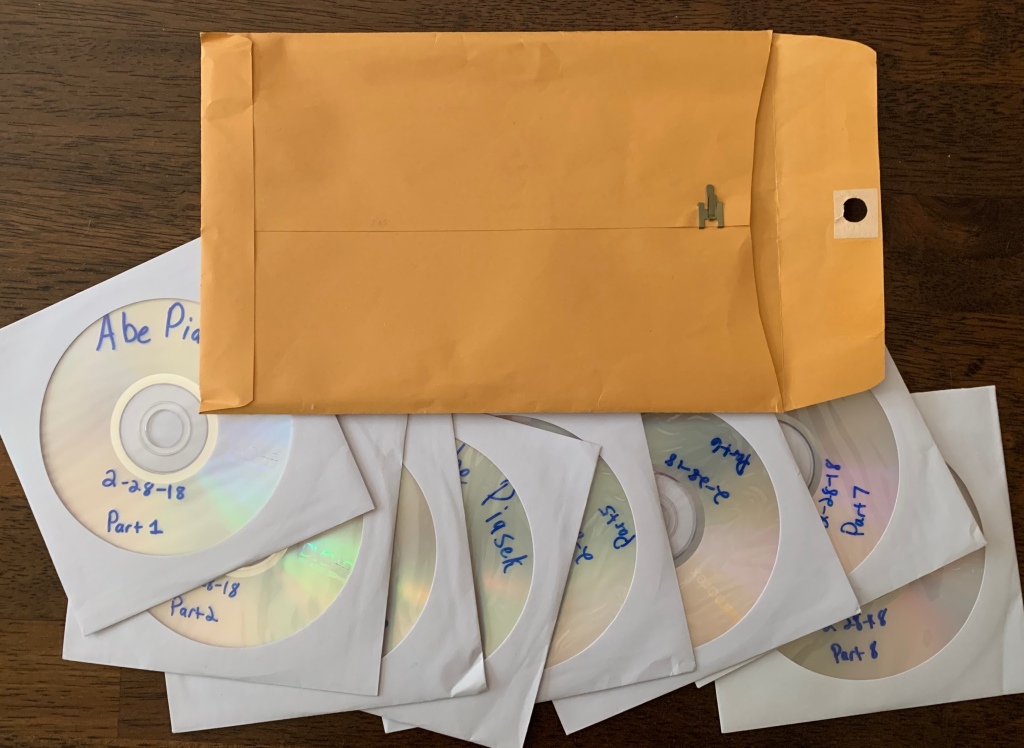

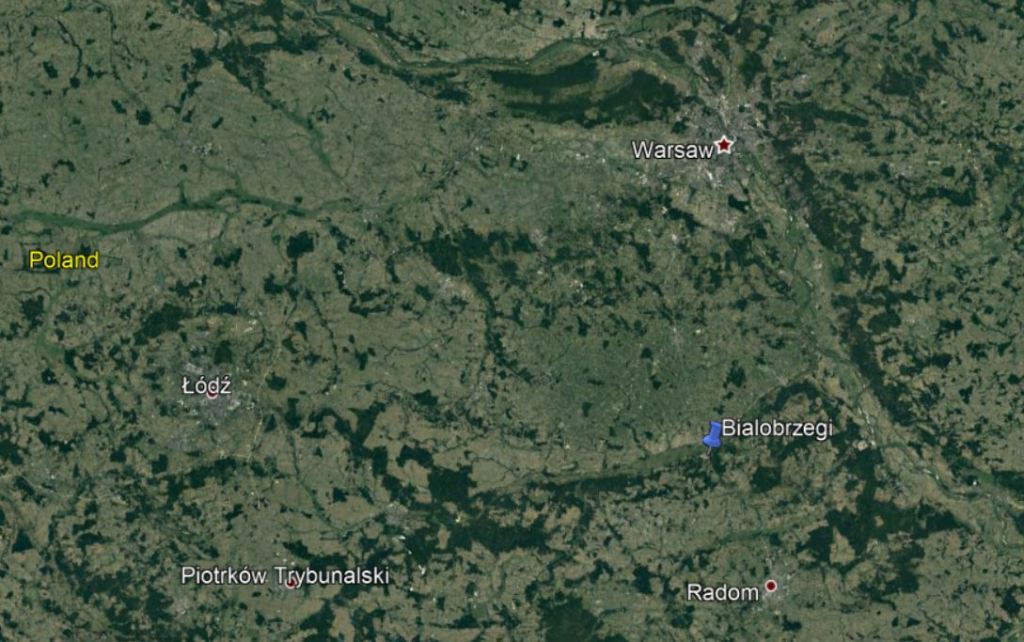

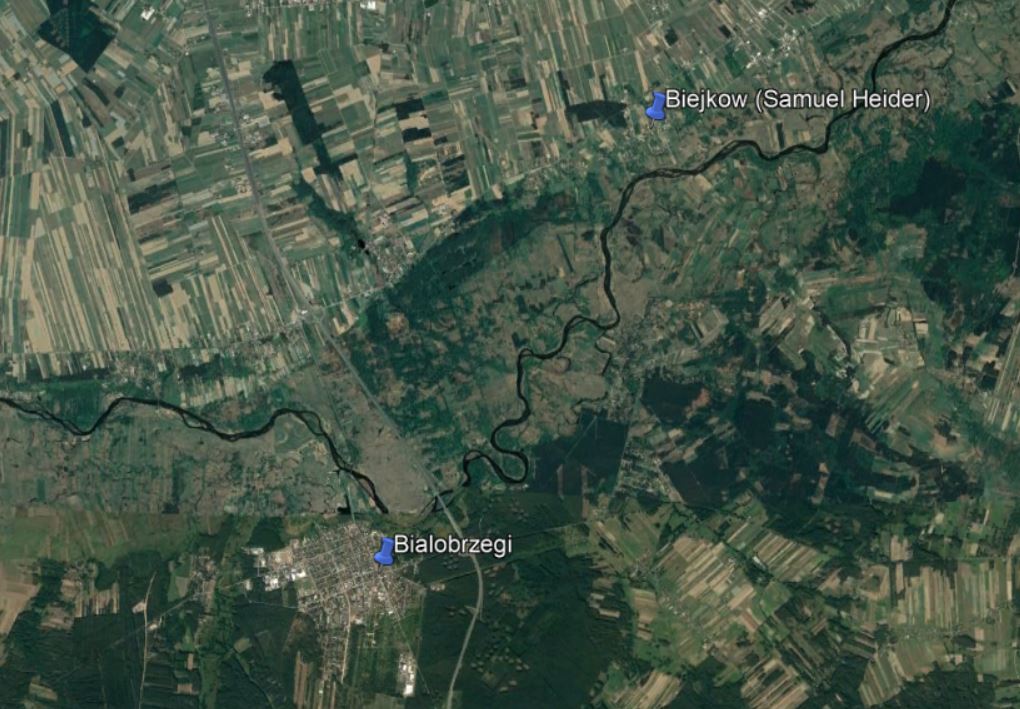

And, because I met Shelly at her home in Greensboro this summer, and talked to her daughter on the phone, I have a personal connection to Rivne. And now Rivne will join Sighet (Elie Wiesel’s home town in Transylvania/Romania) and Bialobrzegi (Abe Piasek’s home town in Poland) as touchstones for me — and for my students — as we learn about the Holocaust.

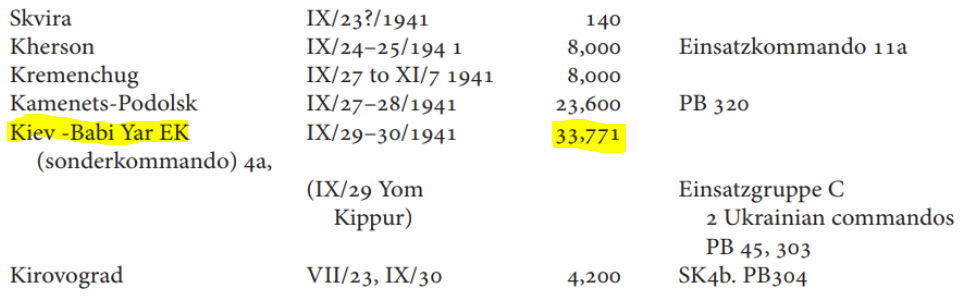

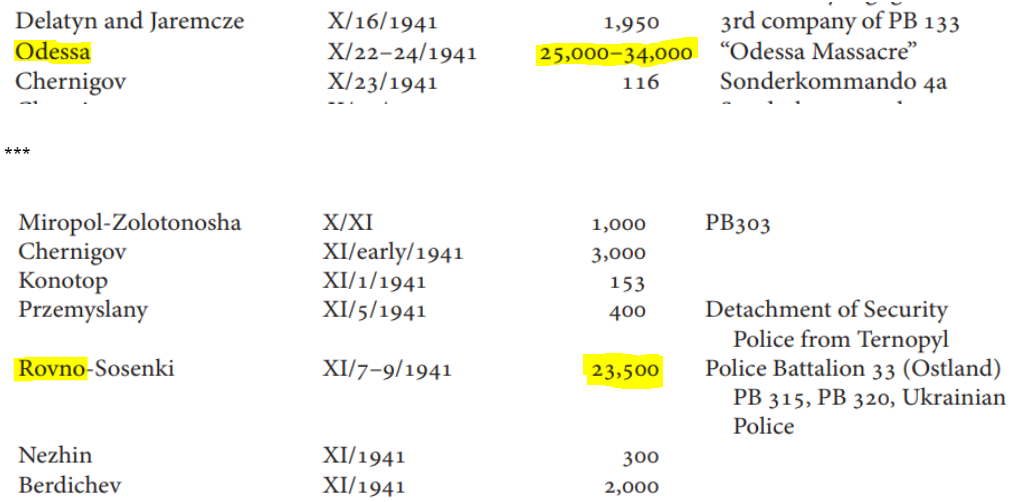

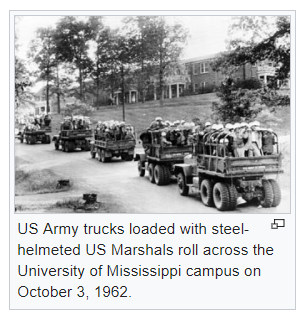

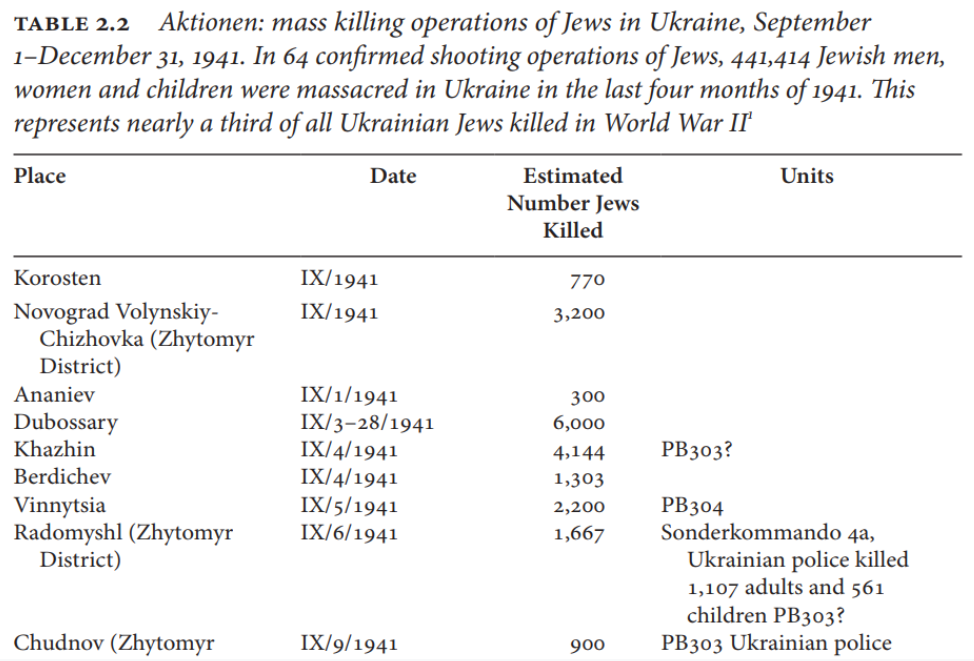

Below is a chart from professor Burds’ book that blew me away. I’d heard of Babi Yar, a well-known massacre of more than 30,000 Jews near Kiev, Ukraine, in September of 1941 — some people consider that the start of the Holocaust. I’d also heard of the Odessa Massacre, another horrific massacre in October of 1941.

But I’d never considered that those massacres were far from isolated events. Professor Burds provides chilling context — there were 64 mass killings in Ukraine the four months of September, October, November and December of 1941, representing more than 440,000 murders.

(the chart goes on for three pages… here are the listings for Babi Yar, Odessa, and Rivne)